“Andes shared an iconographic system, and the extensive use of diverse psychoactive plants, Anadenanthera (vilca, yopo, cebil), tobacco, coca. The enactment of their respective politics, however, differs greatly.”

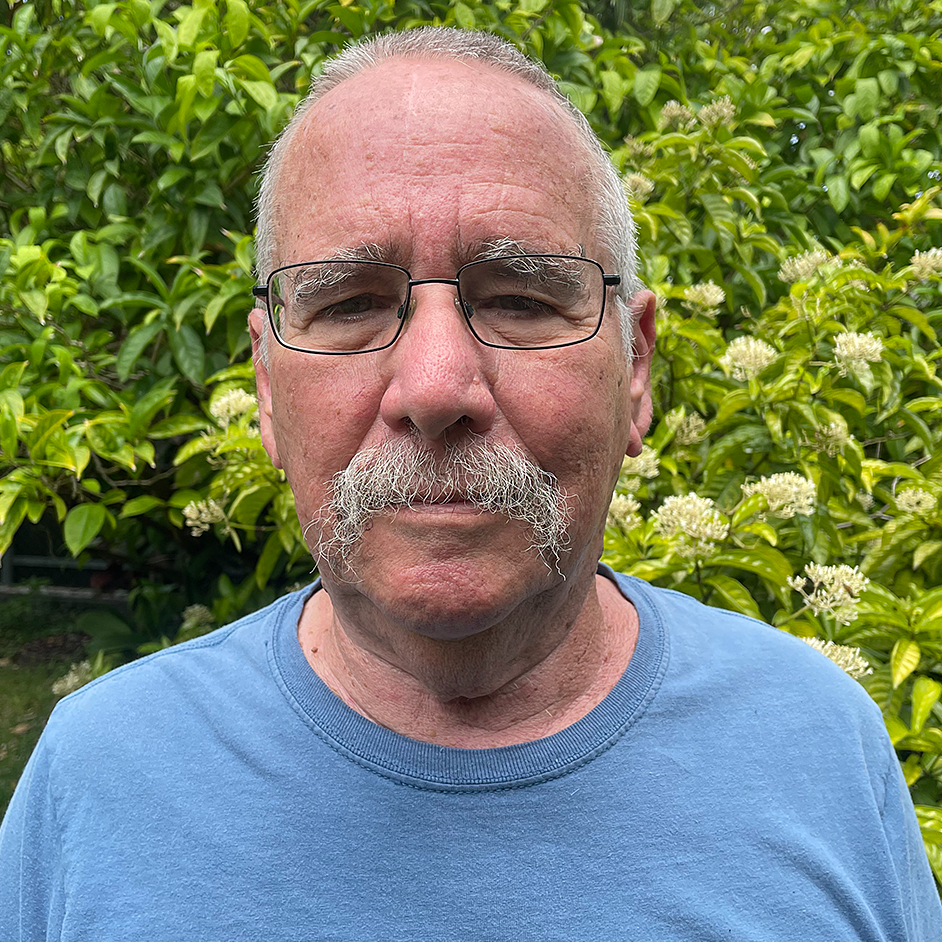

Biography

Constantino Manuel Torres is Professor Emeritus, Art and Art History Department, at Florida International University in Miami. He has conducted research on ancient cultures of the South Central Andes since 1982. His work has concentrated on the San Pedro de Atacama oasis, Chile, and the use of Anadenanthera-based snuffs. His books include Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant of Ancient South America (2006), co-authored with David Repke, a comprehensive and detailed study of this plant in continuous use for the past 4000 years. He has published numerous peer reviewed articles and book chapters. Torres organized several symposia on the art and archaeology of the Andes for the International Congress of Americanists and for the Society for American Archaeology. He has been the recipient of three Fulbright Fellowships.

Tiwanaku and Wari: Psychoactive plants and politics in the Central Andes 300-900 AD.

“In the oasis of San Pedro de Atacama, Tiwanaku mixes with local expressions, as well as with objects from NW Argentina and southern Bolivia, revealing anarchic forms of organizations.”

Transcript Abstract

The presence of objects associated with the Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) and Wari (Huari) cultures define the Middle Horizon (ca. 300-900 AD) period of Andean history. These two pre-Inca cultures of the Central Andes shared an iconographic system, and the extensive use of diverse psychoactive plants, Anadenanthera (vilca, yopo, cebil), tobacco, coca. The enactment of their respective politics, however, differs greatly. Wari expansion is one of colonialist control. In the Wari area there is clear evidence of colonial outposts with the presence of emissaries whose burials mostly consisted of Wari implements, including elaborately decorated textiles, ceramics, and metal objects. Tiwanaku expansion was of a different nature. There is no evidence of colonial envoys, or military enforcement of ideologies. In the oasis of San Pedro de Atacama, Tiwanaku mixes with local expressions, as well as with objects from NW Argentina and southern Bolivia, revealing anarchic forms of organizations. In comparison, Tiwanaku is less hierarchical and less prone to central control than Wari.

The differences and similarities between these two cultures provide the opportunity to observe the impact of psychoactive agents in their respective political contexts. Both use the seeds of Anadenanthera colubrina, rich in bufotenine, as part of their visionary preparations. Tiwanaku favors snuffing and smoking, while Wari favors chicha (beer) de molle (Schinus molle) with the addition of Anadenanthera seeds. They conducted large feasts with serious drinking during which hundreds of litters of chicha with vilca were consumed. There is scant evidence for smoking or snuffing. In the Tiwanaku area of the South Central Andes there is a preference for snuffing and smoking, this is supported by extensive archeological evidence. In the Andes, snuffing paraphernalia is portable and intimate, not likely used in large collective activities. How does the practice of drinking, smoking, and snuffing determine societal configurations? Could the narrative structure of the visionary event correspond to cultural and individual organizational patterns?

.